About 2 in 5 active physicians will be 65 or older by 2034. While many physicians have historically retired closer to age 70, burnout exacerbated by COVID-19 will likely accelerate rather than delay retirement among the current cohort of practicing physicians.

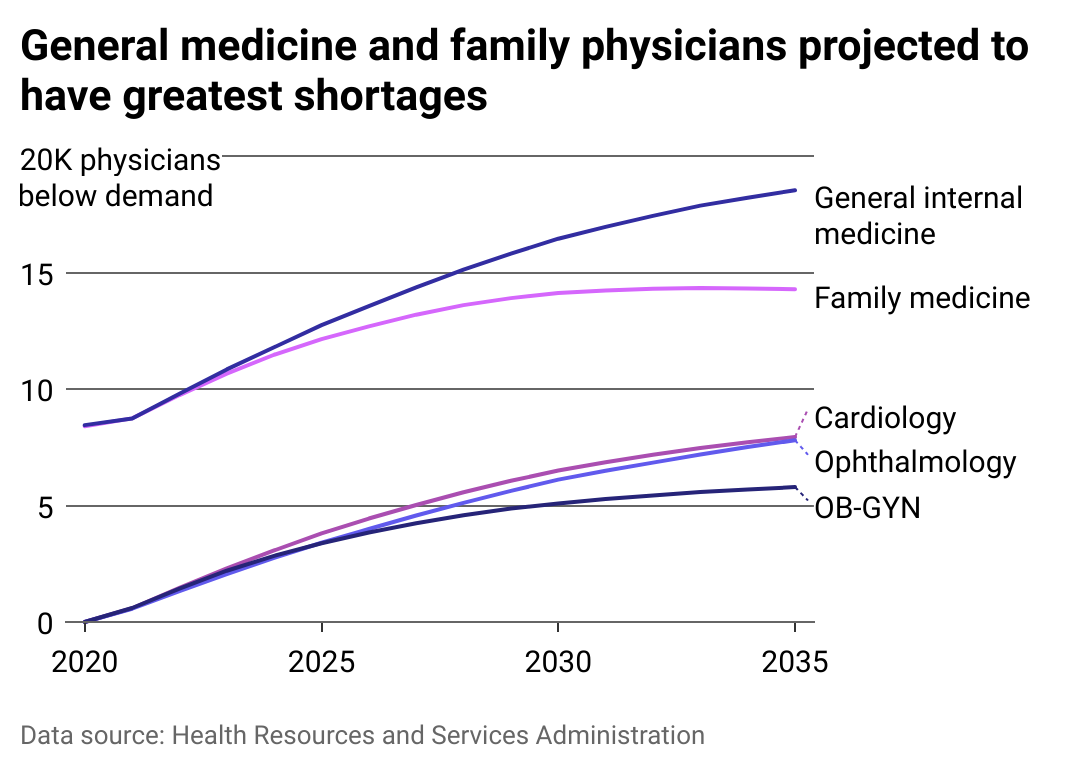

As a result, the United States is projected to be short between 38,000 and 124,000 full-time physicians across all specialties by the end of the decade, according to the American Association of Medical Colleges.

Because it can take at least 10 years to train a physician fully—and in most cases, longer—these decade-long projections require immediate attention if the U.S. hopes to avoid a crisis-level shortage of qualified physicians.

To compound the issue, America is getting older and sicker. Currently, about 1 in 6 Americans is 65 or older. Over the next several decades, this demographic will likely comprise nearly a quarter of the U.S. population. Chronic illness is also becoming more prevalent, driving the need for increased primary care capacity. Eighty percent of adults 65 and older—about 45 million people—have at least one chronic condition, most commonly arthritis, cancer, diabetes, or heart disease.

DocBuddy cited data from the Health Resources and Services Administration to visualize the projected shortages in the health care industry, specifically among physicians.

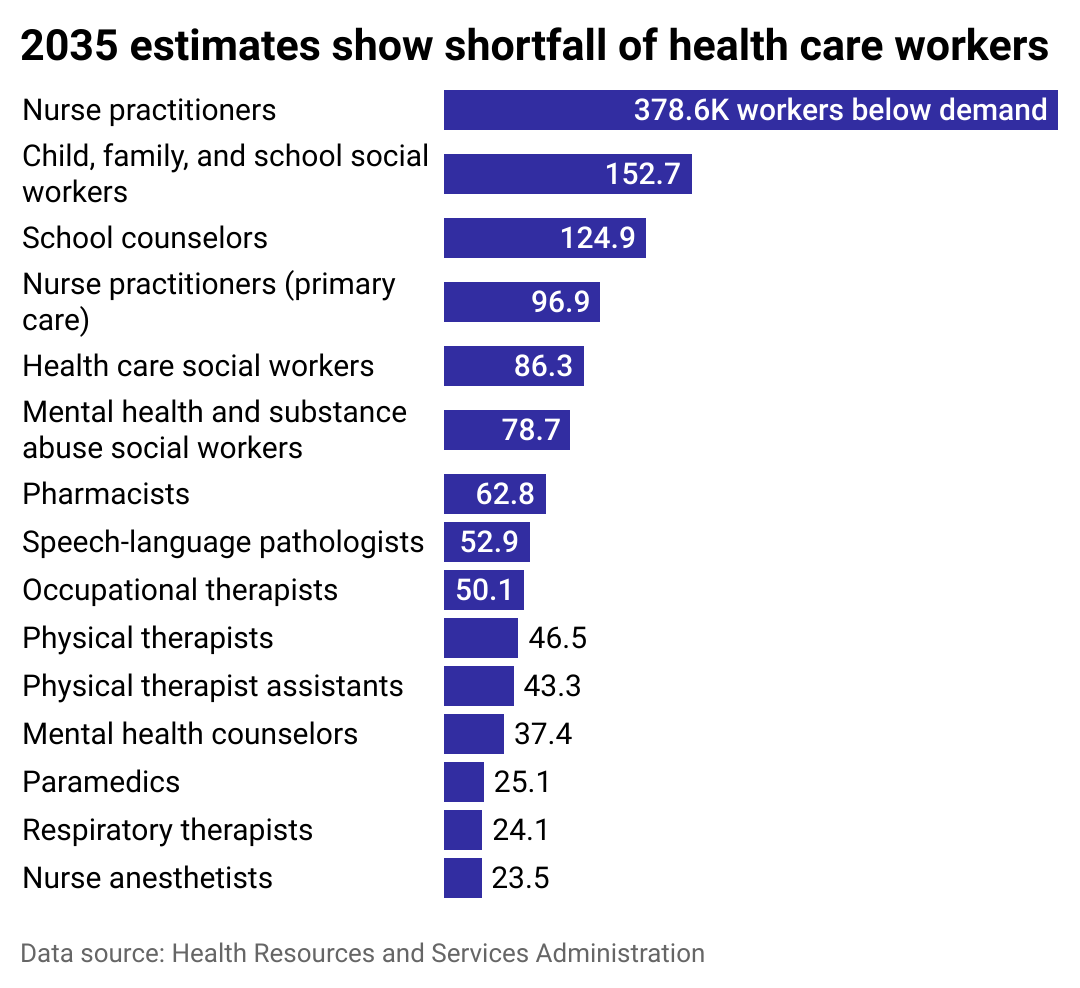

Shortages are projected across the health care industry

It’s not just physicians that are in short supply. The U.S. faces a shortage of nearly every type of critical health care worker, including nurses, therapists, counselors, and social workers. Roughly 1 million registered nurses in the U.S. are 50 or older and will reach retirement age around the same time as many practicing physicians.

In addition to age, stressful working conditions are another driving factor behind the health care professionals shortage. According to the National Academy of Medicine, approximately 35-54% of U.S. nurses and physicians felt burned out before the pandemic. The pandemic exacerbated these stressful conditions, with more than 50% of all public health care workers reporting symptoms of anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

The US could be short over 18,000 general medicine physicians by 2035

A rapidly aging and ailing U.S. population, an aging health care workforce, and pervasive burnout that led to an exodus from the industry are just a few reasons why the U.S. cannot meet health care demands. Limited training capacity and funding are another, as some medical students struggle to get matched with residencies.

In the U.S., there are as many as 10,000 chronically unmatched doctors—people who graduated from medical school but have repeatedly received rejections from residency programs.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are the largest funders of graduate medical education programs such as residencies and internships. However, a provision of the Balanced Budget Act capped funding in 1997. As a result, increased GME program funding has not accompanied patient population growth.

Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and advanced practice registered will likely fill the primary care gap over the next decade.

International medical graduates could fill gaps

According to the American Medical Association, international medical graduates often practice in health care shortage areas serving some of the most at-risk communities. The amount of red tape IMGs must go through, from excessive regulations and immigration applications to difficulty obtaining sponsorship, is a barrier to realizing the full potential of this talented pool of health care providers.

Internationally trained physicians account for more than 50% of all physicians in primary care shortage areas, serving more than 20 million Americans, according to the American Immigration Council. Foreign-trained physicians are also more likely to serve higher-risk populations, including those with lower income, less educational attainment, and those in rural or “health care desert” areas.

Written By Lauren Liebhaber, Data Work By Emma Rubin.

Story editing by Brian Budzynski. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.